My Mingus Immersion

This is a long essay I wrote that appeared in the Mountain Gazette in February 2005, exploring my compulsion to listen to Mingus when I’m driving through national parks and other open landscapes. The piece is no longer available on MG‘s website, since the publication changed ownership hands, so I’m reprinting it here, Ah Um…

Mingus in the Mountains

Mountain Gazette, #111, February 2005

By Joshua Zaffos

I was somewhere around Tower Falls near the heart of Yellowstone National Park when Mingus began to take hold. I remember saying something like, “That’s definitely a wolf retreating into the trees….” And suddenly there was the crash of cymbals and the mashing of piano keys flooding the car, which was going about fifty miles an hour with open windows to Mammoth Hot Springs. And a voice was screaming: “Oh yeah, Oh yeah, Jesus, I know…”

*******

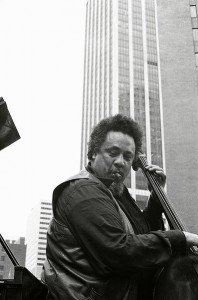

Charles Mingus was a jazz bassist, pianist and composer, one of the most innovative musicians in the genre. His music evokes both Duke Ellington and Johann Sebastian Bach. His songs are ornate and scripted opuses peppered with both compositional virtuosity and emotionally wrought improvisation.

Charles Mingus was a jazz bassist, pianist and composer, one of the most innovative musicians in the genre. His music evokes both Duke Ellington and Johann Sebastian Bach. His songs are ornate and scripted opuses peppered with both compositional virtuosity and emotionally wrought improvisation.

Mingus strived to create music that was an extremely detailed scheme in spontaneity. America’s national parks are similar experiments to Mingus’ balancing act between composition and improvisation. The national park system – as it was conceived in the second half of the Nineteenth Century – is an innovative approach to preserving the natural and wild landscapes of our country in tidy boundaries and structured regulations. It’s a model that the entire world has copied: There are more than 30,000 parks and other protected areas around the globe covering roughly 12 percent of the Earth’s surface. In Yellowstone, remnant populations of Grizzly bears and bison and reintroduced wolves live on, rivers flood and flow freely, and undisturbed geysers burble and erupt.

Of course, just driving through a park leaves a body suspended between the controlled setting of combustion engine-powered vehicle on paved road and the wildness beyond the windshield. I usually listen to Mingus’ late 50s and early 60s recordings on my car stereo at these moments – when I’m driving from fee station to trailhead, visitor center to campground. The composition, “Ecclusiastics,” blares as I spot Canis lupis stretching her legs for the groves of aspen and Doug fir. The music stirs both earnestness and excitement towards nature. Which may be why it sounds so damn good coming out of my speakers in Yellowstone, or any other national park.

*******

Charles Mingus was born in the Sonoran Desert in Nogales, Arizona, on the Mexican border in 1922. His father, a U.S. Army Staff Sergeant, was a mulatto born in North Carolina; his mother was half-English, half-Chinese. When Mrs. Mingus became deathly ill shortly after Charles’ birth, the family moved to the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. She died when Mingus was only eight months old.

In Watts, his father told him he was superior to other blacks because of his relatively light complexion and blue eyes. But on the playgrounds, Mingus was called a “yellow nigger” and his friends were other outcasts including Japanese, Mexican and Italian children.

His father remarried a woman, half-black and half-Indian, who encouraged Charles and his sisters to embrace European classical music and take up instruments. Further stirring the pot of early cultural influences, his stepmother would take little Charles to a “Holy Rollers” church where the choir belted out improvisational big-band gospel music.

He had a trombone at age six, heard his first Ellington record at nine. He switched over to the cello as he approached his teens but eventually began playing bass to gain a seat in the high school band. Mingus listened to Richard Strauss and Claude Debussy while simultaneously discovering jazzman Lester Young and blues guitarist T-Bone Walker. He studied and played with jazz bassists but also learned from symphonic players and attended classical music workshops.

Mingus got his first major studio gigs with Lionel Hampton and Illinois Jacquet in the mid 40s. One reviewer praised the young bassist for “a different style, completely his own.” On one of the first recordings under his own band, critic Ralph Gleason reported that Mingus “has proven there should be no segregation in music between classical and jazz.”

By the 1950s, Mingus started holding “jazz workshops” in New York City. These were mostly jam sessions, according to biographer, Brian Priestly, where Mingus wouldn’t write down any of the compositions for his fellow musicians while “freeing (or forcing) them to interpret arranged passages in a more musical, and more personal way, rather than merely reproducing something fixed.”

Mingus seemed to know he was hitting stride, even if the record companies didn’t. His albums of the late 50s and early 60s (those that provide the soundtrack for my auto-treks through parks) were recorded on a variety of labels. That music evokes church gospel, nightclub jazz standards, big band follies, slave work songs and classical concertos. His works borrow from Charlie Parker, Sergei Rachmaninov and the Gershwin brothers. Drummer Dannie Richmond remembers Mingus schooling him through the bewildering arrangements: “No, at this point you have to whisper, and there have to be other points where there’s planned chaos!”

As he continued to compose, he also advocated for “collective improvisation.” He hated sidemen that couldn’t read music; he hated sidemen that could only read music. He would chew out fellow musicians for repeating a solo.

“‘I’m trying,’ adds Mingus, ‘to play the truth of what I am,’” read the liner notes of his 1962 album, Oh Yeah. “‘The reason it’s difficult is because I’m changing all the time.’”

*******

Nature is changing all the time, too, and in more and different ways than the casual park tourist might recognize after a handful of Yellowstone vacations. There’s a constant transformation at play in the natural world – but we still think of Yellowstone as a fortified and fixed haven of Grizzlies, bison, wolves, bald eagles and cutthroat trout, forever free to roam, soar and swim amid a sheltered environment.

“‘Wilderness’ has a deceptive concreteness at first glance,” writes Roderick Frazier Nash in the prologue of his classic natural history book, Wilderness and the American Mind. The concept of national parks and wilderness areas as neatly arranged parcels of nature insulated from threat reinforces this myth.

According to Nash, the American wilderness movement grew in Eastern cities, where intellectuals romanticized the vanishing, Wild West frontier. Osborn Russell, an 1830s explorer of the Yellowstone region, was mesmerized by the “wild romantic scenery of this valley.” Nash says Russell’s era marked the beginning of an American ethic towards discovering aesthetic value in wilderness, beauty in bedlam. Romantic musings caused wilderness to become part of the evolving American culture.

Intellectuals and artists of that era, most prominently represented by Henry David Thoreau, believed wilderness was an integral ying of American culture if properly balanced with the yang of a civilized and refined society. But Nineteenth Century wilderness appreciation failed to recognize the truly dynamic character of natural landscapes even as it gave birth to a preservation movement. Nash calls the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 the “world’s first instance of large-scale wilderness preservation” and it started a groundbreaking trend towards protecting forests, canyons and rivers and the fish and wildlife that inhabit them. But capturing wilderness in a box, even as big as Yellowstone, is practically absurd.

One example among many is fire management in and around the park. In 1872, everyone assumed that Yellowstone was a wild and pristine environment, existent through the mysterious workings of nature. Nobody recognized the role of Native American tribes in manipulating the landscape through fire. Modern research including studies of tree rings shows that fires occurred up to five times more frequently in the Yellowstone region before settlers pushed the Native Americans out of the area. Fires sparked by the tribes mimicked lightning-caused strikes but were started in order to thin dense young stands of lodgepole pines and regenerate aspen groves for the benefit of wildlife.

The frequent burns also precluded massive infernos. After Yellowstone became a park, the manmade blazes that had created the “wild” landscape ceased. A century of fire suppression created the crowded forest conditions that resulted in the cataclysmic wildfires of 1988. Modern fire management has progressed beyond extensive fire suppression, but at the same time park officials remain wary of more frequent prescribed burns.

In the context of this example, ecologist Daniel Botkin says our mode of thinking towards resource management remains a Nineteenth Century perspective. In his 1992 book, Discordant Harmonies, Botkin says we still choose to protect and manage natural landscapes by merely throwing a fence around them. We treat parks as if they were divine mechanisms that maintain a balance on their own.

Botkin tells the story of elephants in Tsavo National Park in Kenya that, although native to the region, grazed the grasslands to a wasteland when they were unable to migrate outside park boundaries during severe drought. Similarly, when bison herds leave the confines of Yellowstone and cross onto private or state land in Montana, state officials kill them for fear of brucellosis, an infectious livestock disease that bison may carry. The 1988 Yellowstone fires were acceptable and even desired until they pushed outside park borders and threatened private lodges and ranches.

The outdated strategy in parks is akin yet crucially different to Mingus’ musical approach of “planned chaos.” Improvisation, for Mingus, wasn’t just getting up on stage and letting his front line blow. Such spontaneity ironically required frequent gigging to build familiarity over the musical landscape and understanding between the collective parts of the band. And then to assure that each player wouldn’t reproduce the same solo each time but instead let his intuition guide the course through the music. Jazz critic Max Harrison once lauded Mingus because “The unity of his works depends not on their technical organization…but is largely of an emotional order.”

It is the Native American version of fire management – and planned chaos – that more closely resembles Mingus’ experimentation. Botkin laments that we manage by “the analytic and the rational…and tend to deal with nature by freezing it conceptually,” without assimilating “the intuitive and emotive” into management plans. In other words, not only have we failed to account for our scientific knowledge of nature’s dynamic character when thinking about parks and wilderness, but we don’t figure in our emotion and passion for the environment either.

Yellowstone, at 2.2 million acres, is still the largest national park in the lower 48. But landscape ecologists now recognize that a conservation area of approximately 382 million acres – from Yellowstone all the way north to the Yukon, known as Y2Y – is probably necessary to actually preserve the plants and wildlife we hoped to save in the national park.

The increased land base of Y2Y follows wildlife migration corridors and physical watershed boundaries instead of political borders. It also accounts for regional and global pressures on Yellowstone’s localized resources including air pollution from coal-fired power plants, water quality degradation from hard rock mining, and climate change.

*******

Through the 60s and 70s, Mingus continued to experiment between composition and improvisation. His works became larger and more complex, culminating in performances at New York City music halls with 20-person ensembles often freelancing through songs. He was trying to resolve through his music all those varied – and constantly changing – aspects of his self.

“My need is to express my thoughts and feelings as fully as is humanly possible all the time,” Mingus wrote in his manic and sometimes fictitious autobiography, Beneath the Underdog.

Throughout his musical career, Mingus played with Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Blakey, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins and many, many other titans of jazz. He also wrote scores for films and plays, worked with classical composers and even collaborated with Joni Mitchell. In 1972, Mingus undertook an “operatic ballet” of symphonic jazz where the players needed to “compose as they improvise.” “But I want to get to the point where everyone playing something of mine will be able to think in terms of creating a whole,” said Mingus, “will be able to improvise compositionally so that it will be hard to tell where the writing ends and the improvisation begins.”

By the time Mingus died in 1979 of Lou Gehrig’s Disease, he had won a Guggenheim Fellowship and had been honored for his musical accomplishments at the White House by President Carter. And his legacy of jazz experimentation was fully prepared to live on. Today, you can walk into an East Village club, Fez under Time Café, on most Thursday nights and see the Mingus Big Band perform his music. The 14-piece band rotates through more than 40 regular musicians. Sue Graham Mingus, the composer’s widow, oversees the troupe as well as the Charles Mingus Orchestra and she challenges the musicians to continue to honor the vision of Mingus.

Biologists such as Michael Soulé, Reed Noss and Botkin advocate for Twenty-first Century park management that emulates Mingus’ approach to music. Blurring the realms of man and nature, encouraging adaptive and collective management, thinking “in terms of creating a whole.” Despite entrenched paradigms, we are beginning to base our decisions on the constantly growing pool of technical knowledge – but we’re still lacking the “emotional order” that should also drive our protection of wild landscapes.

Most parks like Yellowstone with its Grizzly bears and highway loops are already contradictory organisms. Parks are chaos and plan, garden and jungle, composition and improvisation. For now, they are the largest experiments our society is ready to conduct.

You don’t need to be a Ph.D. ecologist to question the outright wildness of Yellowstone or other national parks. The lines of the boxes are significant constrictions on fire patterns, wildlife migrations and flood cycles. The exit ramp and industrial-sized parking lot at Old Faithful geyser looks more like Newark Airport than a park scenic area. Most tourists take in the landscape through their vehicle windows, hurtling 45 miles an hour on asphalt no different than the Jersey Turnpike. Clearly, I’m also guilty of cruising through our ecological gems; I’ve even gotten a speeding ticket in Yellowstone.

Parks are explicitly for the ever-changing mass of people with their ever-changing values, too. But the miles of paved roads, the visitor centers, guest lodges and concession stands are all tweakings to these packaged natural areas. And the refrigerator magnets, ice cream cones and snow globes are all distractions to the emotions these places call forth in us. Mingus used to stop performances if he felt the audience wasn’t giving him proper attention. The passionate shouts and soaring crescendo of his music override the dulling of my senses that comes from sitting in my car in Yellowstone.

When people finally step out of their vehicles, away from the gift shops and into the forests, they recognize a park as a geographic and biological opus. I too have to get out of my car and turn off the Mingus to truly embrace this idea. I hike up Bunsen Peak, wander along Slough Creek or sneak off to Imperial Geyser to escape the asphalt and the view from behind my steering wheel and cracked windshield. I can travel on crowd-friendly boardwalks or bison trails and recognize chaos and plan, garden and jungle, composition and improvisation, both, neither, everything in between. After all, even Mingus believed that it’s not just two poles that tug at us.

“‘In other words, I am three,’” Charles Mingus began his autobiography.

“‘Which one is real?’” a psychiatrist asks the character Mingus.

“‘They’re all real.’”