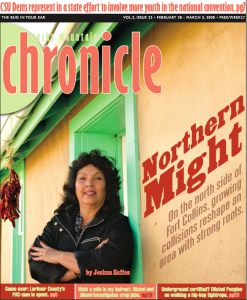

Northern Might

North Fort Collins is separated from the rest of the city by the Cache la Poudre River, a geographic break that historically kept Hispanic and other foreign families segregated from downtown. In recent years, development pressures have initiated a makeover for the north-side, but citizens and city officials remain concerned that changes may impact the social and cultural fabric of historical neighborhoods.

***

Northern Might

A s the north-side makeover continues, longtime Fort Collins residents assert their heritage.

s the north-side makeover continues, longtime Fort Collins residents assert their heritage.

By Joshua Zaffos

Rocky Mountain Chronicle, February 28, 2008

Frank Martinez calls the new Northside Aztlán Community Center “gorgeous.” He repeats the compliment three times during a twenty-minute phone conversation, emphatic in his praise.

And after a tour through the $10 million building, which opened last November, it’s obvious what he means. Light filters through the windows of the expansive open lobby, and the center’s exposed steel and cast concrete purposely evoke an industrial-chic atmosphere. The state-of-the-art construction from energy- efficient components and recycled materials of the former building will probably earn LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification. Bilingual signage and Latin American-inspired artistic elements of glass and concrete fuse the center with a creative display of multiculturalism.

Martinez grew up at the old Northside Aztlán, running around the playground, participating in sports, staying off the streets. “Northside was huge for me,” he says. “It really did give me the confidence to succeed in school and at sports.” After graduating high school and serving in the Army, Martinez came back to work at the center, coaching and mentoring children as he was coached and mentored when he was young. He gave up his job when the new building opened to finish his degree and pursue other work, but he helped hire his replacement. Now Martinez is a member of the center’s advisory council, an unofficial committee that serves as a liaison between the facility and the community.

“I’m familiar with a lot of the insides and outsides,” Martinez says, “and I’m worried about the squeezing out of programs and it not being a community center that is accessible to all people in the community. That’s what made Northside beautiful.”

The difference between “gorgeous” and “beautiful” is a feeling among local families, many of them Latino, that the spiffy, new facility doesn’t offer the same amenities as the old center — or that it does but with prohibitive new fees and rules.

In other words, the multicultural vibe needs to be more than decoration.

Discriminating Geography

Outside the doors of the Aztlán Center, other changes are afoot on the north side of Fort Collins. There are plans for an outdoor amphitheater and a kayak park. Mixed-use developments, combining apartments and “loftominiums” with shops and offices, are popping up all over. Many of them are similarly using sustainable-design elements and being marketed to the cultural “creative class,” coveted by retailers and Realtors. In this context, the north side is an untapped frontier for growth, where Old Town can meld with plans for the city’s Beet Street cultural and arts area.

Since its settlement, Fort Collins has grown south from Old Town, away from the Cache la Poudre River. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Great Western Sugar Company sited its sugar-beet factory north of the river, and farm-labor families populated the surrounding neighborhoods — first Germans from Russia and then Hispanic families from New Mexico and farther south.

German Russian immigrants, unwelcome to live among the general population of Fort Collins, moved into the north-side neighborhoods of Buckingham and Andersonville in the early nineteen hundreds. Mexican Americans later followed and mixed with the German Russians. In 1923, Great Western started a new settlement and provided straw, lime, gravel and lumber for families to build two-room adobe homes. Workers could, over time, purchase a house and property for under $200. Latino residents called the area La Colonia Española. Today, it’s called Alta Vista, and all three neighborhoods are known as the colonias. Adobe homes are still scattered among the blocks, and the area remains — for the moment, at least — predominantly Latino.

Tony Rodriguez’s home in Andersonville sits on the busy corner of Lemay Avenue and Vine Drive, where trains rumble by and cars back up at the intersection all day. As a young boy, Rodriguez moved to Fort Collins with his parents, migrant farmworkers from Texas. Rodriguez and his wife have lived in the home for 58 years, raising five children along the way.

“It was a rough life, let me put it that way,” Rodriguez says of his youth. “I didn’t have an education. I had to start working the fields all over.” He keeps a thin moustache on his thin face, and his creased cheeks are a testament to years of outdoor labor.

North-side residents lived with pollution from the factory and passing trains. The city dump was adjacent to the neighborhoods. River flooding was a looming danger each spring and summer. When the families crossed the river into downtown Fort Collins, they ran into a different set of threats, from prejudiced citizens who refused to associate with them or sell them goods.

Neither the City of Fort Collins nor Larimer County wanted jurisdiction over the colonias, so roads were unpaved and muddy, and houses relied on wood stoves for heat. Into the Seventies, families had outhouses, because the government refused to extend a sewer line to the region. A 2003 historical report for the city (PDF link) calls the area “a geography of discrimination.” In this void, AltaVista elected unofficial mayors to advocate for the most basic services, such as street maintenance and indoor plumbing.

“The town here — the racism was real bad,” Rodriguez recalls. “When we came here, [shop windows] said, ‘No Mexicans, White Trade Only’.” He pauses as his mind fast-forwards to the present. “It’s a little better.”

Over time, progressive citizens advocated for the removal of signs that denied Mexican Americans access to stores. And the north side’s cultural identity finally got a physical home of sorts, when the City of Fort Collins built the Northside Community Center in 1977 at the site of the former landfill.

New and Old Kids on the Block

On a weekday morning, the new Northside Center bustles with kids shooting hoops in the gym and grownups working out with free weights and on treadmills in the fitness center. There’s a Tai Chi class underway and a children’s education program, themed around “Dora the Explorer,” in progress. Other programs teach cooking, Spanish, badminton and Salsaerobics, among dozens of other activities for children, adults and seniors.

The building is two-and-a-half times larger than the old center. The new gym — “the Cadillac of the whole facility,” says city Recreation Manager Steve Budner — has an elevated track around its perimeter and is three times bigger than the former center’s single basketball court.

But they don’t hold any funerals at the new center.

It used to be that every once in a while, if they didn’t have enough money for a loved one’s funeral, a north-side family would approach the staff of Northside Aztlán, which would arrange for a reception at the center, free of charge.

“A lot of the people we’re talking about here have a hard time paying for a funeral, let alone a reception,” Frank Martinez says. He estimates about five to fifteen services used to take place at the old building every year, and the assistance built loyalty toward the community center among residents of the colonias.

Kids under eighteen used to walk in free to the center and spend afternoons playing sports and games. That doesn’t happen anymore either. Now, children ages six to fifteen must pay a dollar to use the new center each day, while teens must pay two dollars. Punch cards for multiple visits do offer cost breaks. “And although it’s just one or two dollars,” Martinez says, “there are kids that I’ve talked to who are not going.”

(A lounge, with pool tables, computers, a big-screen TV and PlayStation, is open for no charge.)

If the fees sound minimal, think of a family with two working parents and two children in need of after-school activities. Now the family must pay $10 a week — $500 a year — for weekday access, a significant amount for people struggling to buy groceries and pay property taxes or rent and utility bills.

The center also offers scholarship funds that reduce fees for children and adults who qualify for federal- or state-assistance programs. But Martinez says some parents who don’t qualify for other government programs still need financial help. Some are overloaded with work or otherwise reluctant to fill out the forms.

Martinez has also heard from children who fear that rates for summer sports programs, including basketball leagues, will be raised. Martinez remembers back when a team used to pay $10 total to enroll to play. Last year in the old facility, each child paid $25 or $40, depending on the league, but higher fees could reduce participation among kids from low-income families.

“It’s a program that’s been used to keep kids off the streets and out of gangs, and it’ll be interesting to see how that works,” Martinez tells me. “It really does create a home for the kids all summer. Hopefully, that’s not lost.”

“A lot of activities were free and it was a good place to find adult leadership and guidance,” Budner says, “and I think we still have that here. The old Northside was a close community. I think this was pretty scary to a lot of people.”

Budner, who has spent 22 years working for the city’s recreation department, has a neat, graying goatee, and today, as we walk around the new Northside, he wears a mock turtleneck and a blue sweater with a city recreation logo. He is disarmingly friendly and not at all scary, but he realizes that he is the face of a new regime (the recreation department is now headquartered at Northside).

The center has no plans to raise summer league costs, Budner says, but he acknowledges that the facility won’t accommodate free funerals or other family services. Everyone must pay $25 per hour for a community room, which includes access to a full kitchen.

Martinez responds that the benefits of waiving costs in the dozen or so cases each year — and the community pride toward the center fostered by the assistance — outweigh the $150 or $200 the city would collect for each event.

As far as the new fees, Budner says the changes bring Northside’s operations and rates in line with other city facilities, although he recognizes the complications regarding the scholarship applications.

“We do whatever we can to get that filled out,” Budner says, including contacting teachers when parents are unavailable. “We do not turn anyone away.” He says he’s also encouraging longtime staff to reach out to children who formerly used the center but haven’t shown up to the new space.

“I think we’re seeing more new faces than old faces,” Budner says. “We’re glad to see the new faces, but we don’t want to lose the old faces either.”

A Brewing Storm

If there is an industrial face to the north side these days, it’s New Belgium Brewing Company. Since 1995, the enviro-friendly microbrewery abuts the Buckingham neighborhood at Linden and Buckingham streets. (The sugar beet factory site is now the city’s streets department headquarters.)

Upstairs from the brewery’s tasting room, its flowing taps and overflowing crowd, Kim Jordan, New Belgium’s CEO, keeps her office where the sounds of clinking glasses and buzzed conversation provide background ambiance.

“I love this neighborhood. We moved here because we love this part of town,” Jordan says. “But sometimes it makes me sad, because I feel like it’s not as integrated with New Belgium or the downtown.”

The disintegration, as it were, of the north-side neighborhoods has bubbled up in a few standoffs in recent years. The Rocky Mountain Sustainable Living Fair, which happens one weekend every September at the “Oxbow” property, bounded by both New Belgium and Buckingham, has faced criticism for clogging neighborhood streets with parked cars. New Belgium’s Tour de Fat, an annual bike parade and carnival of sorts that brings out thousands of costumed bicycle riders and beer drinkers, has also drawn complaints about noise, traffic and public intoxication. And sounds from the brewery’s late-summer, bike-in movie series in its parking lot are said to echo through the neighboring streets.

If the colonias still elected a local mayor, Betty Aragon-Mitotes would probably be the perennial frontrunner. She has lived, on and off, in Buckingham since the 1960s, and she is a frequent spokeswoman and ambassador for the neighborhoods. She led local opposition to a truck-bypass route and helped build support for the purchase and preservation of the Romero House, an adobe home in Andersonville, as a museum of local Hispanic culture.

Aragon-Mitotes says the events and crowds, despite their green credentials and philanthropic motives, are noisy shake-ups to a neighborhood that has long suffered a range of affronts and injustices. But her concerns also ring as a preemptive, defensive stance against proposed development.

The Bohemian Foundation, under the control of local billionaire Pat Stryker, owns the Oxbow and has plans to build an outdoor amphitheater on the property, which could regularly host concerts and events, attracting thousands of people through Buckingham, on a nightly basis for months. Aragon-Mitotes says the constant crowds would be a major imposition on the neighborhood, and she’s even more worried about the venue triggering an increase in property taxes, which would price out longtime residents who get by on fixed incomes or modest wages.

“The music venue is the most important issue facing the Buckingham neighborhood,” Aragon-Mitotes says.

Bohemian Foundation staff and a project design firm met with local residents in April 2007 to talk about plans. (The Coloradoan ran a below-the-fold, front-page article about the meeting; the above-the-fold front-page story on a looming snowstorm had an ironic headline: “Brewing storm could whiten city.”)

Merry Hummel, the Bohemian Foundation’s executive director, says, via email, that plans for the Oxbow are still conceptual, and the organization plans to meet again with neighbors before submitting its plans to the city.

“We don’t have specifics to share at this time, but we are committed to talking and working with our neighbors,” Hummel writes. “As you may know, the Bohemian Foundation believes in creativity, imagination and spirit and is dedicated to improving Fort Collins, and our plans for the Oxbow will focus on this mission.”

Infill, Then Move Out

Anne Aspen of the Fort Collins planning department walks into our meeting at the city offices on North College Avenue carrying an armload of rolled-up maps. She unrolls them all, and we focus on one that frames the north side of the city.

From a bird’s-eye view, north Fort Collins looks vastly open. Huge parcels of vacant and former agricultural land surround the colonias. On Aspen’s map, every sizable chunk of green space is labeled, in Sharpie, with the name of a prospective development.

A development with 163 residential units is already undergoing city review. A conceptual project, in the early stages, would include about a thousand residential units and another 270,000 square feet of commercial real estate, right next to Alta Vista. Another conceptual development could build low-density, high-end student housing designed to look like single-family cottages. An open lot along Vine Drive, near Conifer and College, isn’t markered, but Aspen tells me a “major retailer” is interested.

The North College corridor, heading out of Old Town, is the city’s “most promising and underserved area for growth,” says Mike Jensen, of Fort Collins Real Estate. “I’d love to be a property owner in those neighborhoods, because they’re going to make out.”

The expansive redevelopment, plus a number of urban-infill loft projects, requires some infrastructure overhauls. The city has already spent $10 million on control measures to reduce flood-prone property and open up parcels to commercial and residential development. Next, the city plans to realign Vine Drive and expand the street’s intersection with Lemay Avenue. The expansion alone will cost around $20 million, and its impacts on Andersonville, including Tony Rodriguez’s home, aren’t clear.

“There’s a lot of culture and a lot of pride in these neighborhoods, and it’ll be interesting to see if these people will get forced out,” Frank Martinez says. “People look and say, ‘That’s low-income, that’s rundown.’ To the people that live there, it’s home.”

The colonias are already seeing an infusion of young couples and individuals looking for reasonably priced property near Old Town. That isn’t a bad thing — to have a new and diverse next generation of homeowners who appreciate the neighborhoods. But it’s likely that nearby quarter-million-dollar lofts and a new wave of shopping centers will also inflate property values — and taxes — among the colonias, which could, over time, eliminate affordable housing in the area.

Jensen says it’s important not to displace the “fiber and fabric of these neighborhoods.”

“I think everyone is pretty committed to [affordable housing] and sustainable and environmentally conscious growth,” he adds.

Betty Aragon-Mitotes isn’t quite so optimistic. She walked away from the affordable-housing task group of UniverCity Connections, a partnership among city-government officials, Colorado State representatives and civic boosters, because she thought the discussions were focused on student housing, not accommodations for low-income families.

The task force has suggested, preliminarily, that one-fifth of new housing along the Mason Street Corridor, which is slated for a public, bus-rapid transit line, should be affordable. Mixed-use projects in Denver and Boulder already lock in below-market-priced units to rent and own. Whether Fort Collins city officials and developers will support the targets when the time comes — and the case can be made that it already has — is another thing. New and under-construction loft projects around downtown have hardly any price-restricted housing.

“We have every right to be in this community, and I feel like we’re being pushed out,” Aragon-Mitotes says. “Is that what Fort Collins is about? Becoming a city for the elite? I’ve heard that my neighborhood is not going to be around in five years.”

Moving History Forward

None of this is unique to Fort Collins. It’s just another case of gentrification in America. But the especially distressing part for our city is that much of the north-side growth is catering to the so-called creative class, the progressive and environmentally conscious people who drink microbrews, watch independent films, shop at farmer’s markets and bike instead of drive — the people who are supposed to embrace community diversity among incomes and cultures.

“I’d like to think that, too,” Kim Jordan says of the targeted populace, when I raise that conundrum and ask if she thinks the decline of the colonias’ culture and affordability is inevitable.

“The future? To me it is, Can we be extraordinary?” Jordan says, with a daring tone that would just sound like rhetoric if she hadn’t launched New Belgium as a model for sustainable and profitable business. “I think we’d lose a lot in turning our backs on recognizing the Hispanic contribution to Fort Collins, and the same thing goes for the agricultural contribution.”

But hope is not yet foreclosed upon.

Aragon-Mitotes and others are trying to raise funds to build an interpretive center next to the Romero House museum to accommodate funeral services and other family events in the future. The city is also considering a playground, basketball courts and a park at the streets department site that was once the beet factory.

Most significantly, neighborhood discussions have begun to consider landmark designation for the colonias. Residents met with city staff, including Anne Aspen and Karen McWilliams, the city historic preservation planner, in November to talk about options, including the differences between protection of individual adobe homes, and others that represent the “vernacular architecture” of the neighborhoods, versus recognition of entire blocks.

Landmark preservation would recognize the area’s history and create financial incentives for homeowners to rehabilitate and repair houses, McWilliams says. It would also provide greater protection against out-of- sync development next to the colonias and prohibit property owners from demolishing structures from within designated boundaries. (Some residents have questioned whether preservation status could also have negative effects, banning some renovations.)

Aspen hasn’t heard of any interest in specifically targeting the colonias for a full-scale makeover. A developer would be “stupid” to do so, she says.

Aragon-Mitotes is drumming up support among neighbors and hopes to submit an application for city historical preservation soon.

“The recognition they’ll receive in the public realm will be huge,” McWilliams says. “I think it will be a great source of pride for the communities themselves. Finally, after years, Fort Collins will formally recognize their contributions, instead of them being an afterthought.”

The reality is that, despite the anxieties and setbacks, the culture and character of the north side are still visible among the homes of the colonias and even the design of the new Northside Aztlán Community Center. Fort Collins is perched at a moment when the city can decide how to identify and incorporate these elements, beyond old and new architectural designs.

“There was a lot of history in that old facility, and we want to bring that history forward,” Steve Budner says of Northside Aztlán. “We have the ability to impact the lives of so many people and make a positive impact for the rest of their lives. That’s what we had at the old Northside, and we want that here.”

In Frank Martinez’s mind, the connections between accessible community center and thriving community are inseparable.

“I think the center is very symbolic of the north side,” he says. “I count it as a resource, where people can come together, where they can meet and they can work. It’s always been a little heart of north Fort Collins. That’s how I view it as a center, and that’s how I view the future.”