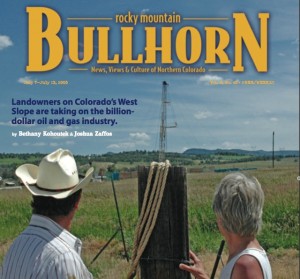

Health problems. Environmental degradation. A billion-dollar business with ties to the White House. Landowners on the West Slope are fighting back against the oil and gas industry.

By Bethany Kohoutek and Joshua Zaffos

Rocky Mountain Bullhorn, July 7, 2005

Laura Amos wakes up in the middle of the night and shuffles from the bedroom of her log home to her computer desk upstairs. She looks in on her 4-year-old daughter, Lauren, as she sleeps, and then sits down at the keyboard to read through technical reports from government commissions and energy corporations. Sitting in front of a glowing computer screen at three in the morning isn’t how Laura expected to spend her nights when she moved to Silt, Colorado, in 1992 to help her husband run his hunting and fishing guide service, Winterhawk Outfitters.

Laura Amos wakes up in the middle of the night and shuffles from the bedroom of her log home to her computer desk upstairs. She looks in on her 4-year-old daughter, Lauren, as she sleeps, and then sits down at the keyboard to read through technical reports from government commissions and energy corporations. Sitting in front of a glowing computer screen at three in the morning isn’t how Laura expected to spend her nights when she moved to Silt, Colorado, in 1992 to help her husband run his hunting and fishing guide service, Winterhawk Outfitters.

She steps away to her backdoor and stares off at the glowing bulbs of gas wells that surround her and drown out the stars. These aren’t the lights Laura pictured filling the night sky around her 30-acre ranchette. Less than 100 yards away, a compound of six gas wells flares and lets out fumes. She turns to see the 10,000-gallon tank that looks like an industrial dumpster and holds her family’s drinking water. Laura thinks of her sleeping daughter and goes back to the computer.

The water well on the Amos’ property became mysteriously contaminated four years ago, at the same time the gas industry was setting off mini-explosions of pressurized water, sand and toxic chemicals to get at natural gas beneath her neighbor’s land. The process, known as hydraulic fracturing, or frac’ing (pronounced “fracking”), increases the amount of recoverable oil or gas.

While in Kansas visiting Laura’s parents with their new baby, the Amoses got an unexpected call. A metal cap had blown off the water well after it erupted like a geyser. They returned home to find their tap water undrinkable.

“The water bubbled like 7Up, and it was a goopy gray,” remembers Laura, as she sits inside Winterhawk’s office on Grand Avenue in the small town of Silt. “After a few days, it had this much sediment”—she holds her forefinger and thumb an inch apart and refers to a glass of water—“and an oily sheen on top.”

A large banner proclaiming “Support Our Troops” hangs in the office window, and the walls are decorated with photos of clients and their trophy kills. A picture of Laura hugging a cougar she killed with a crossbow greets visitors when they walk through the door.

The fizzy and noxious water flowing from her faucets turned out to be saturated with methane gas. The gas industry denied any connection between Laura’s undrinkable water and the well explosion. And it wasn’t until four years later that the state regulatory body, the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, finally linked frac’ing to the water contamination.

“We felt abandoned by the commission,” says Laura, “and abused by the industry.”

Immediately after the contamination, EnCana, the oil corporation performing the frac’ing, provided fresh drinking water in giant tanks for Laura’s family. But that stopped after a few months, and the Amoses had to seek out potable H20 on their own.

In January, after four years, the company resumed its weekly water deliveries. A few months later, the oil and gas commission finally issued a violation to EnCana. By then, Laura had developed an even more critical problem. Two years after the water well blew its top, Laura became curiously yet critically sick. Her doctor eventually diagnosed her with a rare adrenal tumor, which was removed in July 2003. She’s convinced the illness was linked to the frac’ing chemicals she ingested.

“And what was my daughter exposed to?” Laura asks now. It’s one of those questions that keep her awake at night.

Laura isn’t alone among obsessive insomniac landowners living in Garfield County these days. Landowners around the towns of Silt, Parachute and Rifle all can gaze at well pads and drill rigs from their property. Most locals hold only the deed to the land on top while oil and gas companies own the minerals below. The arrangement gives the energy industry the upper hand to build roads and erect gas wells, visibly—and some say, permanently—altering the West Slope’s landscape and environment.

Laura Amos and her neighbors are finding out it’s not a bargain. Frustrated by a no-holds-barred industry backed by a presidential administration that many locals have supported at the polls, these landowners are rising as a new, unlikely class of environmentalists ready to fight back. And they’re quickly learning what they’re up against. After all, Halliburton Services, where Vice President Dick Cheney was once CEO, pioneered frac’ing, and the Veep’s 2001 energy task force pushed to exempt the process from any governmental regulation.

“Billion-dollar industry,” says Laura of the oil and gas companies. “Million-dollar lobbyists, connections to the White House.”

Garfield County is currently home to 2,500 active gas wells—more than any other county in the state. And with 1,000 new drilling permits expected by year’s end, it seems the region’s energy boom is just beginning.

Oil companies are now extracting more than a billion dollars’ worth of oil and gas from beneath the soil of Garfield County each year. And much of that is tapped from private land, like Laura Amos’.

Because Colorado’s Western Slope, particularly Garfield County, has been handpicked by the Bush administration for rapid oil and gas development, the gate to the county has been thrown wide for the petroleum industry. The sheer density of drilling activity in Garfield County is greater than anywhere else in the world; oil producers are authorized to bore wells twenty acres apart—and they’re pressing for an even-tighter ten-acre density allowance.

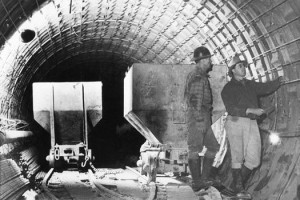

Before a company can drill a new well, a qualified geologist must suspect that oil or gas is lurking below the surface, says Ken Wonstolen, general counsel for the Colorado Oil & Gas Association, an industry trade group. Once that’s established, industry workers (most of whom are out-of-towners; employees are rarely hired locally) raze a two- to four-acre “pad.” The company then erects a drilling rig that augers deep into the earth—anywhere fron 2,000 to 15,000 feet deep—to reach the prized resource.

The towering rigs, which protrude conspicuously from Garfield County’s rugged landscape, competing with the expansive mountain vistas, are the most visible and ubiquitous reminder of the oil industry’s footprint on the region. Of all the extraction machinery, rigs are the noisiest, and their lights cast an orangish light into the night sky—“like a carnival,” as one local activist put it.

While the rigs are an annoyance to the Amoses and other local landowners, it isn’t the tower itself that makes them lose sleep. It’s the next step in the process.

After the hole is dug, hydraulic fracturing fluids, or “frac’ing fluids”—essentially, water laced with chemicals—are injected into the well to force the earth’s natural faults and creases to expand, making it easier for the gas to flow to the surface. These additives can include, among others, benzene, diesel and 2-BE, the frac’ing chemical that Laura Amos believes caused her tumor.

Wonstolen says frac’ing is “essential” in the West, because of the nonporous nature of the tightly packed, sandy soil. EnCana utilizes the process in 100 percent of its well operations within the county, says Florence Murphy, a company spokeswoman.

And both Wonstolen and Murphy maintain that the practice is perfectly safe. In fact, Wonstolen says allegations of contamination, like the Amoses’, amount to a “phony issue.”

Wonstolen contends that 2-BE is found in Windex and other household cleaners; what’s more, only “tiny, tiny” amounts of such chemicals are pumped into the ground, he adds. Otherwise, frac’ing doesn’t involve anything worse than water, sand and gelling agents like guar gum, which is a natural plant derivative. One industry official likes to point out that guar gum is an ingredient in Snickers bars.

And the Environmental Protection Agency backs him up.

In June 2004, the EPA released a rule stating that frac’ing fluids pose “little or no threat” to drinking water. A provision in President Bush’s energy bill, which is working its way through Congress, would permanently exempt frac’ing from any regulation, including the Safe Drinking Water Act.

This particular exemption is plucked from the wish list of the 2001 energy task force convened by Vice President Cheney, who has collected more than $500,000 in deferred salary from the energy giant Halliburton since taking office. The Supreme Court allowed Cheney to keep the task force’s proceedings secret, but the Los Angeles Times retrieved confidential records that hint otherwise.

Cheney’s office, a resulting Times article shows, pressured the EPA to portray frac’ing as a benign process, and to suppress concerns from EPA scientists over the accuracy of the June 2004 regulations.

When asked whether EnCana would support increased regulation and reporting of the frac’ing process, Murphy says the EPA is a “sound regulator.”

Over the past year, several independent organizations have taken the EPA to task over its rule. The Durango-based Oil and Gas Accountability Project produced its own report. “We found that EPA removed information from earlier drafts that suggested unregulated fracturing poses a threat to human health,” it reads, “and that the Agency did not include information that suggest fracturing fluids may pose a threat to drinking water long after drilling operations are completed.”

Carol Bell is standing in an unfinished room that will one day become her writing studio—she hopes. She and her husband, Orlyn, have lived on this rugged and rural acreage outside of Silt for the past 24 years, raising kids and horses, and farming hay.

The couple planned to construct their dream home on their land and retire here, and the new building is already half-completed. That was before EnCana installed four wells on the Bells’ 110 acres, before they endured three explosions on or near their land—one that coated their field in paraffin wax spiked with hydrocarbons, another that spilled 2,000 gallons of diesel, and another that leaked frac’ing fluids onto the well pad—and before they watched their road morph from a quiet country drive to a heavily traveled EnCana thoroughfare (“We counted 22 trucks in one hour’s time,” Bell says).

Today, Carol Bell throws open the giant picture windows of their new home, affording grand panoramas of the mountain ranges that wrap the horizon. She points to them in succession: “The Bookcliffs—and just beyond that, we can almost see the Roan Plateau—the Hogbacks, the Flat Tops Wilderness Area, White River National Forest.”

The room smells of sawdust and freshly mown hay. But don’t be fooled, she warns.

She takes a few steps out of the building and toward the drilling rig just past her barnyard, and the usual farm aromas turn rancid.

“Methane,” she says. “Can you smell it?”

With two dogs trotting close at her heels, the petite woman with cerulean eyes and suntanned shoulders heads toward the rig. She stops and rubs her forehead. Late last night, she admits, she broke down and cried.

“The last three nights, the odor was terrible. Oryln woke up with a splitting headache. It’s so awful. We can’t sleep. We’ve had it,” she says. “But no one will buy this place. … [Drilling] just takes your property value to zero.

“It’s sad, and I hate to [move], but Orlyn just turned 60 and…” she trails off.

In early 2004, EnCana approached the Bells about drilling on their property. Already,rigs were sprouting up on the land adjacent to their farm, and they’d heard inklings of other families’ struggles with the oil industry. They immediately hired a lawyer.

When Carol and Oryln Bell bought the ranch a quarter-century ago, they purchased only the surface rights, not the claim to the resources underneath; the previous owner refused to sell the mineral rights. At that time, no one knew that this pristine and remote swath of Western land would later become the epicenter for a battle over oil and gas.

Under Colorado’s “split-estate” laws, oil companies are permitted to drill on private land, as long as they give the surface owner a 30-day notice. If the company and the landowner fail to reach an agreement about compensation and well placement, the company can post a one-time bond of $2,000 for dry land, or $5,000 for irrigated land.

Unlike the Bells, some Garfield County residents own both the surface and the mineral rights to their land. While they have an advantage over surface-only owners (mineral deed-holders receive monthly royalty checks from the oil companies), they, too, have little say in where wells and roads are situated, or how they’re cared for.

Often, “They just bond on and bring the bulldozers over,” Carol says.

Some state lawmakers are determined to level the playing field. Rep. Kathleen Curry, a Democrat from Gunnison, attempted to restore balance to the split-estate conundrum when she introduced House Bill 1219 this session.

The measure would have required companies to work with property owners to determine a fair compensation for any damages incurred by drilling.

It also took a harder line on the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission. Many West Slope landowners charge that the commission is tangled in ties to the industry and takes a soft stance on violation enforcement.

“They [the commission] rely too heavily on staff,” says Duke Cox, president of the Grand Valley Citizens Alliance, an environmental activist group that has been outspoken in its criticism of the oil industry. “We believe the staff leans almost always toward industry. We are the outsiders in this equation, because we’re rocking the boat.”

But it was the industry that made waves over Curry’s bill, and HB-1219 eventually was defeated in committee.

EnCana opposed the legislation, spokeswoman Murphy says.

“The thinking behind the bill—and we applauded and recognized the need for improvement in the way the industry dealt as a whole with private landowners—was that there already are regulations in place, and we’re not certain that putting another level of regulations in place would be the solution.”

Landowners in other states, however, have been more successful. Wyoming recently passed a tougher split-estate law, and lawmakers in New Mexico and Montana are crafting comparable legislation. And U.S. Rep. Mark Udall, a Boulder Democrat, has expressed interest in introducing a similar measure at the federal level.

After battling EnCana for nine months over specifics like where to place the wells and pipelines so they wouldn’t interrupt the ditch irrigation system or the horse-grazing pastures, the Bells finally signed “out of duress.” Carol Bell says: “It was hell.”

The couple eventually received a one-time payment that Carol Bell deems “minimal.” She estimates EnCana siphons millions of dollars’ worth of oil from their property alone.

The experience has changed their lives, she says, as well as their political outlook. From the window, she points out at Orlyn, perched atop a tractor, mowing the hay fields. Before their experience with EnCana, he declared himself a staunch Republican. While he hasn’t joined his wife on the roster of the Grand Valley Citizens Alliance, he’s much warier of the Bush administration and how its energy policies are playing out in his backyard.

And there’s more like him, conservative ranchers, shop owners, outfitters, construction workers who’ve watched their fields, their air quality, their property values—and some believe, their health—sacrificed to a tidal wave of drilling and extraction. In the midst of a red county that selected Bush as its choice for the country’s highest office in 2004, the Grand Valley Citizens Alliance’s membership has climbed from 75 two years ago to more than 300 today.

“When an industry takes $1.3 million of value from under our feet, we’re not going to take it,” Cox says. “People here are angry—very angry.”

Carol Bell is well aware of the national imperative to beef up oil and gas reserves. She understands that the issue casts tentacles into domestic security, foreign policy, the Iraq war, and the price she pays at the pump. She just wants some balance—and some assurance that the land she’s tended for 24 years won’t be permanently marred when the oil has dried up and the companies move on.

“[EnCana] has a right to be there, they absolutely have a right,” Bell says. “But I think property rights should be equal to mineral rights. … They don’t have the right to come out here and destroy our clean water and air. They’ve taken everything this property is about, and everything we love about this property.”

“We tried to say, ‘We can live with this. We can handle this,’” she says. “But now, I just don’t know.”

Laura Amos doesn’t know what not to do. One morning, she drives off to Denver to sit in on an industry conference on frac’ing, and then cruises back home to attend an evening meeting of the Grand Valley Citizens Alliance. A day later, the woman who’s informally been deemed the “Erin Brockovich of the West” spends her morning showing the area to reporters; the following day she meets with Democratic Sen. Ken Salazar’s Western Colorado aide. Every night, insomnia rouses her prematurely, and she works at her computer.

In April, Laura visited Washington, D.C., and spoke with Congressional aides and representatives from across the country, including the offices of Sen. Salazar, Democratic Rep. John Salazar and Rep. Udall, from Colorado. Her trip paid off two weeks later when Sen. Jim Jeffords, an Independent from Vermont, introduced legislation to require the EPA to regulate frac’ing chemicals through the Safe Drinking Water Act. Sen. Salazar is considering signing on.

While Amos’ story clearly had an impact in Washington, she isn’t the only one making sure her voice is heard in the Beltway.

Last October, Weston Wilson, a 30-year-veteran environmental engineer in the EPA’s Denver regional office, raised a series of questions about frac’ing. In an eighteen-page letter to the agency’s Inspector General and members of Congress, Wilson claimed the EPA’s rule failed to consider studies that showed frac’ing fluids could indeed contaminate underground drinking water. He also raised concerns that industry reps, including a technical advisor from Halliburton, dominated the scientific review panel.

The EPA is still looking into Wilson’s charges, but the whistleblower was recently sent from Colorado to Africa, where he was temporarily assigned to work on a project unrelated to the oil and gas industry. Meanwhile, new EPA Administrator Stephen Johnson spoke at the annual meeting of the Western Governors Association in Breckenridge this June and said, “Rather than the EPA being a stumbling block for energy development, I want it to be a catalyst for energy development while protecting the environment.”

Conservation groups concerned that environmental protection has become a secondary priority to energy development for the EPA are finding some new grassroots allies among the landowners of rural Garfield County.

“It’s the rape of our American West by the oil companies, with absolutely no focus on conservation,” says Cox of the Grand Valley Citizens Alliance. “And the Bush administration’s response to the problem is to drill more wells. We’re mad as hell and we’re not going to take it.”

Industry analysts recently predicted that Garfield County will be pocked with more than 10,000 wells by the end of the decade. It’s news like this that reinforces a unique bond that has developed between camps more accustomed to being at odds with one another.

“What an alliance this is creating,” marvels Carol Bell. “Environmentalists and ranchers are teaming up together.”

The Grand Valley Citizens Alliance and its members say they’ll continue to fight for regulations on frac’ing, monitoring of groundwater quality and evenhanded contracts between surface-rights and mineral-rights owners. The Bells have decided to dig in their heels and win some concessions from the industry rather than surrender their retirement plans just yet. The Amoses, on the other hand, are ready to get out and relocate—even if it means turning over their property to the mortgage company.

“We have an unusable, unsafe piece of property that is un-sellable,” Laura Amos says. “That’s the situation the state and industry has put us in.”

In October, the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission will hold a hearing to determine the fine against EnCana for the ongoing contamination of the Amoses’ water.

EnCana’s Murphy says the reason for the hearing is “so that everybody can put their facts on the table.”

But Laura is quick to point out that the commission is not addressing the safety of frac’ing fluids, only the undisputable fact that her well was tainted. And it won’t appease her in her quest to get to the bottom of what happened. She isn’t taking anyone’s word that Windex and Snickers are responsible for her contaminated water and her battle with cancer.

“We probably wouldn’t be so bitter if they just became accountable and said ‘Yeah, we f’d up,’” says Laura. “But all’s they do is lie and deny.”